Some drawings are done as finished products, others are sketches, that is to say, trial pieces made toward the creation of finished works and thus representing stages in the artistic creation. Or else they are exercises, like quickly executed life drawings done in the studio. Sketches are therefore tentative; as such, they are private works.

They are nevertheless exhibited publicly today in galleries and museums; and they are auctioned and sold and resold and collected as works of art. Like many critics and collectors -- presumably most of them -- I have a deep appreciation of drawings, sketchy or polished, especially those by artists who were or are great draughtsmen and -women.

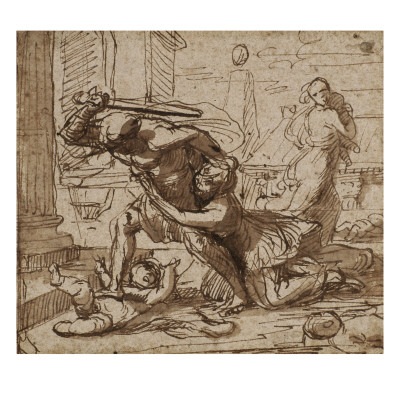

But when I started to think about the appeal of artists’ sketches, I began to realize that this is a very curious phenomenon. We think, of course, that sketches are valuable. They reveal the artist’s process of thinking and assist us in gaining a better understanding of the works toward which they were made, however sketchy they may be, however slapdash, slipshod, shabby. Through the sketches the artist informs us of her/his initial idea and the ensuing tribulations -- uncertainty, indecisiveness, doubts and reversals -- before reaching the eventual solution achieved to her/his satisfaction. The value in this regard is biographical, and it is inherently different from the artistic value we find in the finished works of art. It has to do with our encounter with the artist, rather than the consummate works themselves seen apart from the person of the artist. A sketch drawings by an anonymous author whose finished works are unknown is no lead to the artist’s mind and is of interest only for the quality of the piece and must be appraised as such. The literary counterpart of the sketch is the draft or work in progress, which is exhibited or published for their biographical interest, not really for their literary merit. The rehearsal for a play and other performing arts may be opened to the public but it is never mistaken for a finished performance. It is only a rehearsal, a tryout to test the work, a step toward the completion. Drawings are treated like finished works of art.

Sketches are predominantly works on paper. But there are oil sketches and underdrawings, sculptors’ wax and terracotta models, known variously as bozzetti, modelli, and maquettes, and full-size drawings for murals, called cartoons. They exist in those cases where a high degree of deliberation is required in creating the finished work, and, therefore, a careful advance planning. There are, on the other hand, those works of art which require supreme craftsmanship and yet lack the trail of drawings leading to their completion. They may not have been made; and, if they were, they were discarded as valueless. Works of ceramics immediately come to mind but also of silverware, glassware, lacquerware, jewelry, tapestry, basketry, and other works that are generally classified as craft rather than art. Craftspersons are not artists, so goes the presumption, and whatever preparatory work that went into the making of the final work, carries no biographical interest. The finished products count, not the makers -- not as much. A half-baked bowl is not of much use, nor tattered tapestry.

We know of the conspicuous paucity of drawings surviving from the 15th century. It is not that Quattrocento artists didn’t draw; sketches were discarded as trash when the work was finished, unless they were deemed reusable as a model for apprentices or for later projects that required a similar design. The underdrawing for a fresco was obliterated under the finished work; the cartoon for it was thrown away. But a new aesthetic outlook developed early in the 16th century. Michelangelo’s cartoon for the Battle of Cascina, an unexecuted fresco project in the Palazzo Vecchio, was so revered and coveted by his pupils and followers that it was cut into pieces and distributed among them as a model and a treasure. Thus, through the sixteenth century, master artists’ drawings were saved and collected by younger artists as well as collectors more and more for the inherent value placed in them as products of great creative minds. Vasari, later in the century, spoke of the sketchy drawing as endowed with the spark of creativity made visible as never possible in the studiously finished work. Artists themselves nonetheless considered drawings are preparatory, even though they saw in those of the mastery traces of an inspired mind.

The 20th-century sensitivity valued spontaneity as an aesthetic merit of highest order. It represents the outpouring of the artist’s unadulterated creative energy free of deliberation. It bespeaks the artist’s innate genius. Eventually, any scribble from a great artist’s hand came to be considered of artistic value, not merely of value as a document of a creative process. The focus of our aesthetic interest has shifted totally from the pleasure given by a carefully deliberated and finished work to the glimpse into the mind of the artist as a unique individual. The process, therefore, became more interesting than the well-made product, more essential a feature of art. The works of some Abstract Expressionists fully demonstrate the aesthetics of the process passing as the product. A splashy smear of paint is seen as expressive, and by that account beautiful, but only if the person of the artist, her/his ego, holds something worthy of being expressed.

In the 21st century, we find indications that the tide is changing. We see more works by younger artists today for whom deliberation seems more challenging and satisfying than spontaneity, more essential a feature of art. The product, more than the process, is becoming the goal of their aspiration.

In the 17th century, Poussin argued that imagination is a natural property of any of us. We all can fantasize and create faries, phantoms, and chimeras; imagination is rampant. The artist’s special gift is the power to give fantasy a consummate form by composing them into a tightly integrated work, To many of us today his sketches show verve and vitality and are more appealing than his seemingly frozen compositions. For him sketches were only sketches. Indeed they are.

No comments:

Post a Comment