The opera Lulu at the Met in its new production by William Kentridge was an exuberant spectacle, dominantly his than of its composer Alban Berg. Despite Marlis Petersen’s superb performance in the title role, both in singing and acting, and the powerful music under the direction of Lothat Koenigs replacing indisposed James Levine, what remained in memory was the dynamic stage display of Kentridge’s design, rapidly and incessantly changing sets composed of fragmented flats, video images, placards, masks, and the brushed drawings in process coming out of Kentridge’s own hands. The belief underlying the production, no doubt, is opera as Gesamtkunstwerk as conceived by Richard Wagner. I contend nonetheless that what distinguishes opera from other forms of music theater is singing to which other artistic endeavors are certainly not to be subservient but stay eager participants. Kentridge’s so-called chamber opera at BAM earlier, Refuse the Hour, was this artist’s similarly dense multimedia spectacle but it succeeded totally because he was his own ringmaster.

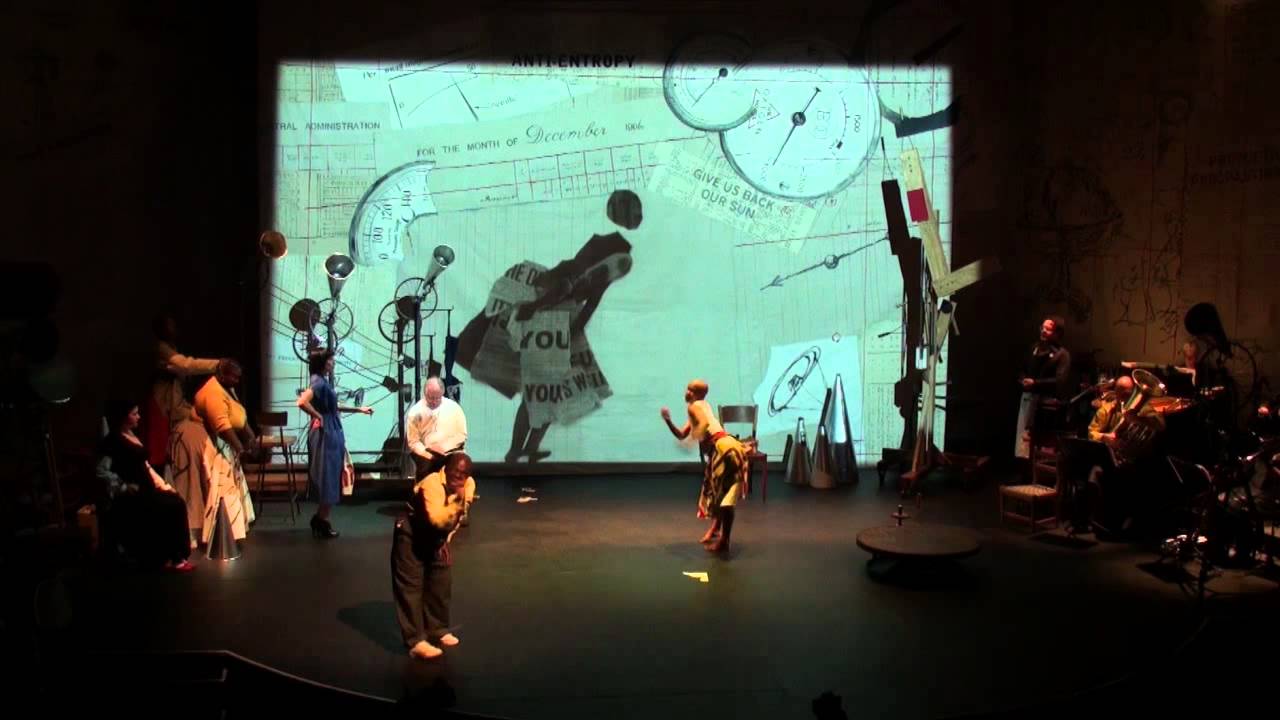

It dealt with a complex idea of time, temporarity, and memory, resulting from his consultation and collaboration with the physicist Peter Galison, and the ensemble of dance, music, and singing performed on stage and the remote-controlled set of drums suspended from the loft, and Kentridge’s own sketches and collages and film clips, together with his recitation of the libretto text he wrote, worked dramatically together to expose the mystery of time — time arrested, reversed, accelerated, decelerated, elasticized, fragmented, and otherwise distorted.

But the spectacle similarly overlaid and orchestrated was just too much for an opera production, domineering our attention excessively. Kentridge also introduced two extraneous non-singing characters, non-singing, therefore, additional visual distractions, a butler character who flittered across the stage every so often and a young woman, nominally a pianist, who sprawled on the piano most of the time and occasionally making choreographed poses. What I found sorely missing is the clearly defined mise-en-scene for the three acts, set successively in Vienna, Paris, and London, marking Lulu’s progressive degradation. After several viewings, with the visual novelty wearing out, we may learn to pay less attention to the stage and concentrate on the music and singing. But I suspect it will take more than a few years of repeat performance. William Kentridge is a great artist, visionary and inventive in his conceit, broad and profound in his socio-political perspectives, and most adroit in realizing them. His work on Shostakovich’s opera The Nose was admirable no less than his earlier efforts Il ritorno d’Ulisse and Die Zauberflöte. It is a pity that there was no one to restrain him in this latest effort.

It dealt with a complex idea of time, temporarity, and memory, resulting from his consultation and collaboration with the physicist Peter Galison, and the ensemble of dance, music, and singing performed on stage and the remote-controlled set of drums suspended from the loft, and Kentridge’s own sketches and collages and film clips, together with his recitation of the libretto text he wrote, worked dramatically together to expose the mystery of time — time arrested, reversed, accelerated, decelerated, elasticized, fragmented, and otherwise distorted.

But the spectacle similarly overlaid and orchestrated was just too much for an opera production, domineering our attention excessively. Kentridge also introduced two extraneous non-singing characters, non-singing, therefore, additional visual distractions, a butler character who flittered across the stage every so often and a young woman, nominally a pianist, who sprawled on the piano most of the time and occasionally making choreographed poses. What I found sorely missing is the clearly defined mise-en-scene for the three acts, set successively in Vienna, Paris, and London, marking Lulu’s progressive degradation. After several viewings, with the visual novelty wearing out, we may learn to pay less attention to the stage and concentrate on the music and singing. But I suspect it will take more than a few years of repeat performance. William Kentridge is a great artist, visionary and inventive in his conceit, broad and profound in his socio-political perspectives, and most adroit in realizing them. His work on Shostakovich’s opera The Nose was admirable no less than his earlier efforts Il ritorno d’Ulisse and Die Zauberflöte. It is a pity that there was no one to restrain him in this latest effort.

No comments:

Post a Comment