Thursday, January 17, 2013

Blotched Golden Age

Gold, blotched, may still glitter, and so does Terrence McNally’s Golden Age, a farce that portrays an impromptu opera behind the stage involving fictional Vincenzo Bellini, his star soprano Giulia Grisi and other singers between their stage appearance in his latest The Puritans (that is, I Puritani). The conceit holds a lot of promise. McNally, who loves opera, was obviously having fun. But the play as staged looked like a first draft, impromptu in that sense, too, prolix and poorly paced. The fault may be the director’s, though I expect better from Walter Bobbe.

Actors were awkward; Lee Pace playing Bellini, in particular was annoying with his mannerism on which he relied to capture the composer’s neurosis. Comedic lines drew titters from the audience; acting was not raw enough to excite guffaws, and it was not restrained enough to bring about pathos. The different cast in the playa’s 2009 Philadelphia premiere, which had Marc Kudish as the baritone Tamburini, might have delivered a better performance to judge by the reviews. Only when Bebe Neuwirth as Maria Gilbran occupied the stage the play was enlivened; when she was joined by George Morfogen as Rossini near the end of the play, was there finally a drama. I didn’t mind the historical inaccuracies that bothered some critics; the present-day conversational style in the delivery of lines may have worked if better articulated. The best thing in the production was Santo Loquasto’s set. I enjoyed McNally’s Master Class (1995) with Tyne Daly as Maria Callas and The Stendhal Syndrome (2004); but of his plays I have seen I thought the top best was Dedication, or the Stuff of Dreams (2005), no doubt brightened by the participation of Nathan Lane and given weight by great Marian Seldes.

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Haneke's Amour

Michael Haneke’s latest film, Amour, is a gracious downer gracefully crafted. It is a story of an aging husband as a caretaker of his slowly declining wife, too familiar to too many and possibly too painful for many in the audience to watch. Yet it is interminably engaging, deeply felt, and long remembered. Haneke eschews melodrama by preparing the viewers to go slowly. How he does it impressed me most of all.

He opens the film with a pre-credit scene of Georges's dead body discovered by firemen breaking the doors into the couple’s apartment; he places the narrative conclusion at the outset (as Hitchcock often does) and he does so to prevent us from chasing the narrative as a suspense (unlike Hitchcock). The body lies peacefully, and we are given no clue as to how he died. In the first scene after the credit, we see a concert hall straight on in a long shot staying on for a long time so as to allows us to scan and take time to find Georges (whom we have seen so far only briefly) and Anne (whom we have not yet seen), listening intently to Chopin being played on the stage off screen. He thus trains us to watch the film without rushing, in the pace simulating effectively Anne’s slow physical deterioration. Then, through the course of the film, he maintains preference for static camera and long takes; the camera’s intense gaze, unblinking and caressing, records meticulously and matter-of-factly the mundane activities of caring with the same tender patience of Georges looking after Anne, paying the same close attention to details as he does and thereby making tactile without sentimentality his deep genuine love for her.

At the time of filming, Jean-Louis Trintignant in the role of Georges was 81; Emmanuelle Riva as Anne, 84. I barely recognized him from his screen image I was familiar with from 1969/1970: Z, Ma nuit chez Maud, and Il conformista. I could not recognize her at all from Hiroshima mon amour (1959) or even from Kieslowski’s Blue (1993). To see them was a special pleasure; but their performance was totally stunning, as impressive as Haneke’s direction, and so was Isabelle Huppert as the couple’s alienated daughter.

Monday, January 14, 2013

Golden Season

How odd, this winter, the theater season offered four golden titles. It started out with David Henry Hwang’s Golden Child, which dealt with the pangs of modernization from one generation to the next in a Chinese family. There was Terrence McNally’s play, Golden Age, recreating a backstage opera involving Vincenzo Bellini, There is Clifford Odet’s celebrated Golden Boy, about a boxer, which I will not see. The most satisfying, for me, was The Golden Land, the Folkbiene’s English-Yiddish musical by Zalmen Mlotek and Moishe Rosenfeld, about Jewish immigrants in the first half 20th century, beautifully sung and performed, heartwarming and touching.

Krymov's Dramatic Invention

Dmitry Krymov from the Moscow Theatre School of Dramatic Art brought to St. Anne’s Warehouse in Brooklyn his two-part production, Opus No. 7. I found his inventiveness phenomenal. The spectacle was magical as it is hard to describe.

Part I, entitled Genealogy, was a dirge to the persecuted Jews who perished under Stalin; Part II, Shostakovich, meditated on the tribulations of the composer, denounced time and again, and humiliated even when honored by the State. Both deployed reading, mime, music, dance, singing/chanting, photography, film projection, acrobatics, painting/smearing, puppetry, and installations, and the effect they achieved was sad, now melancholic now sinister, occasionally funny, and ironic throughout.

The theater’s black box was divided lengthwise to set off the bleachers seating on one side so that the stage is a lengthy floor in the 1:4 proportions. The set consists only of a patchy crudely constructed 8-ft. plywood panels running full length at the back. The first dramatic moment, which also introduces the subject, happens when the seven actors of the cast -- three men and four women -- line up with a bucket of black paint, which they splash on the plywood wall. The smear makes shadow figures, which the actors then complete by stapling sleeves and yarmulke (one with painted peyos), accompanied by the vocalise of the singers among the actors, high soprano and deep baritone, and at times by a horn. When the figures are complete, arms come through the sleeves supplied by actors behind the panels, making the mockup figures appear like ghosts of the perished Jews, and the fictive and real people join hands and dance a hora. A little later, eye glasses appear pressed out from slots on the plywood wall, and the actors paint bodies to make silhouette images of children arranged like a class picture. Then, there is an explosion that shake the theater and a blast of newspaper chips blown from behind the wall fall on the audience and fill up the whole place, the stage and the bleachers. They also contain photographs and negatives. When the negatives are held up to the projected light lifesize figures of orthodox Jews appear on the wall between the shadow figures, and the photographs soon turn into moving images. Another dramatic moment follows when a prowling SS officer projected on the wall kicks a pram, and with a bang a real pram is pushed out through a hatch piled high with baby shoes. Some actors pick up pieces of papers and read names of relatives and friends and describe their idiosyncrasies. Speeches are in Russian; but subtitles are almost superfluous. With minimal words, the drama is powerfully felt and understood.

In Shostakovich, Mother Russia is a huge puppet, like those of the Bread and Puppet, ample and magnanimous in appearance but tyrannical in action, manipulating Shostakovich, a bespectacled diminutive actress comporting the boyish look of the young composer; he escapes from the grip of the puppet and escapes into the crude plywood model of a grand piano, the only prop on the floor. Later he runs away around the stage from the handgun aimed at him and at one point hides within the audience. Toward the end, he is honored with a medal which is mounted on a dagger which pierces his body and kills him. His public statements, often ironic or otherwise quoted ironically, are read voice-over in Shostakovich’s own voice to outline the incidents in his life. Mother Russia clasps the dead body on her laps; but in the end she is shot from the back and collapses like a mound in center stage. Both plays accomplished a political theater without politically rhetoric -- a contrast to the Public’s earlier presentation, Nathan Englander’s discursive The Twenty-seventh Man.

It was an event with a deeply felt lasting impact; it will not be easily forgotten. A Vimeo of the play in four parts -- two hours long -- is currently available on line.

Part I, entitled Genealogy, was a dirge to the persecuted Jews who perished under Stalin; Part II, Shostakovich, meditated on the tribulations of the composer, denounced time and again, and humiliated even when honored by the State. Both deployed reading, mime, music, dance, singing/chanting, photography, film projection, acrobatics, painting/smearing, puppetry, and installations, and the effect they achieved was sad, now melancholic now sinister, occasionally funny, and ironic throughout.

The theater’s black box was divided lengthwise to set off the bleachers seating on one side so that the stage is a lengthy floor in the 1:4 proportions. The set consists only of a patchy crudely constructed 8-ft. plywood panels running full length at the back. The first dramatic moment, which also introduces the subject, happens when the seven actors of the cast -- three men and four women -- line up with a bucket of black paint, which they splash on the plywood wall. The smear makes shadow figures, which the actors then complete by stapling sleeves and yarmulke (one with painted peyos), accompanied by the vocalise of the singers among the actors, high soprano and deep baritone, and at times by a horn. When the figures are complete, arms come through the sleeves supplied by actors behind the panels, making the mockup figures appear like ghosts of the perished Jews, and the fictive and real people join hands and dance a hora. A little later, eye glasses appear pressed out from slots on the plywood wall, and the actors paint bodies to make silhouette images of children arranged like a class picture. Then, there is an explosion that shake the theater and a blast of newspaper chips blown from behind the wall fall on the audience and fill up the whole place, the stage and the bleachers. They also contain photographs and negatives. When the negatives are held up to the projected light lifesize figures of orthodox Jews appear on the wall between the shadow figures, and the photographs soon turn into moving images. Another dramatic moment follows when a prowling SS officer projected on the wall kicks a pram, and with a bang a real pram is pushed out through a hatch piled high with baby shoes. Some actors pick up pieces of papers and read names of relatives and friends and describe their idiosyncrasies. Speeches are in Russian; but subtitles are almost superfluous. With minimal words, the drama is powerfully felt and understood.

In Shostakovich, Mother Russia is a huge puppet, like those of the Bread and Puppet, ample and magnanimous in appearance but tyrannical in action, manipulating Shostakovich, a bespectacled diminutive actress comporting the boyish look of the young composer; he escapes from the grip of the puppet and escapes into the crude plywood model of a grand piano, the only prop on the floor. Later he runs away around the stage from the handgun aimed at him and at one point hides within the audience. Toward the end, he is honored with a medal which is mounted on a dagger which pierces his body and kills him. His public statements, often ironic or otherwise quoted ironically, are read voice-over in Shostakovich’s own voice to outline the incidents in his life. Mother Russia clasps the dead body on her laps; but in the end she is shot from the back and collapses like a mound in center stage. Both plays accomplished a political theater without politically rhetoric -- a contrast to the Public’s earlier presentation, Nathan Englander’s discursive The Twenty-seventh Man.

It was an event with a deeply felt lasting impact; it will not be easily forgotten. A Vimeo of the play in four parts -- two hours long -- is currently available on line.

Saturday, January 12, 2013

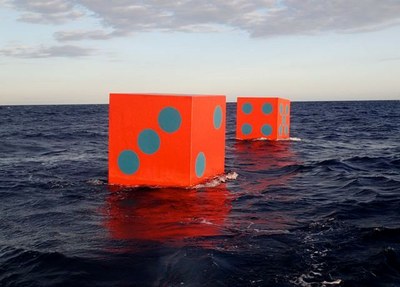

Aqua Dice

Max Mulhern, now residing in Paris, designed and launched a pair of Aqua Dice -- 8 ft. dice of plywood, painted red and blue and equipped with GPA systems into the Altantic Ocean last December, auspiciously on 12/12/12, from the Canary Islands. The project reminded me of Mallarmé’s masterpiece Un coup de des jamais n’abolira le hasard, which happened to be one of his inspirations. To congratulate him, I wrote two pommes;

Aqua Dice forever adrift

now slow now swift

ever chance's gift?

Aqua Dice continues afloat

ever more remote

asymptote.

Check out the NYT article, “An Artis's Game of Chance on the High Seas,” and the YouTube “Aqua Dice Sets Sail.”

Marclay's Clock

Christian Marclay’s Clock makes us live aware of every minute of each hour minute by minute with a shot or a short sequence of shots culled from a vast array of films, old and new, mostly American. It was first exhibited at Paul Cooper Gallery in Chelsea back in February 2011. Last week I sat through two and a half hours of its 24-hour loop at MoMA from 9:35 to 12:05. To say it was an enthralling experience is understating it.

The film is composed of at least 1440 pieces of film, if we count one shot a minute, each with a timepiece of one sort or another -- a clock or a watch, or else, spoken words saying the time; but actually it contains at least twice that number in all because there are shots without any timepiece, too. The sheer task of

compiling and splicing them is a heroic act of patience. But, above all, the continuity that accomplishes a semblance of narrative is truly breathtaking. For example, a woman knocks at an apartment door; the cut shows the interior and a man opening it but this is from another film. Similarly, a man starts a car, checks his watch, and then the next shot shows another car speeding on a highway with a different character at the wheel from another film. A woman pours tea but another woman drinks it in different setting of another shot. Different segments from one film are at times distributed over a length of passing time, some without a time piece in it, but always synchronous with the real time regardless.

Ideally, one should view it in its entirety, all day and all night, or at best, say, from 5:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. continuously. Otherwise, one should catch in two to three hour segments several times to cover as much of the whole film. A DVD version of the film would be impractical without a means of synchronizing it with real time. But a catalogue raisonnée listing all the filmic sources minute by minute would be useful for film buffs, for whom the work is an inexhaustible source of pleasure. Even within my two-and-a-half hour of viewing, I recognized, without being able to identify immediately, numerous films from my stock of knowledge. It was a tremendous pleasure to encounter familiar faces of actors from the past, near and remote, even if, again, I was unable to quickly remember their names since the shots are flashed only instantaneously and go fast.

In the course of two-and-a half hours we are also made aware of the situations when we are alert to the elapsing time; awakening in the morning or from a nap, waking someone up, going to work or school, waiting for and catching a bus or train, a rendezvous of all kinds -- an appointment, a date, a tryst, a conference, a meeting, and any consorted action requiring the watches to be synchronized, completion of a task, looking up a large clock in a public place, like the Big Ben, and later in the day, getting up to start cooking dinner, checking on the return of a family member, remembering a TV program to watch, the movie showtime, or a curtain time at a theater, preparing to hit the sack, and waking up in the middle of night. Conversely, we are reminded of those instances when we forget the passing of time as when we are deeply engaged in work, play, reading, or daydreaming.

Daydreaming, indeed, quite aptly describes the experience of watching Christian Marclay’s cinematic masterpiece, Clock.

The film is composed of at least 1440 pieces of film, if we count one shot a minute, each with a timepiece of one sort or another -- a clock or a watch, or else, spoken words saying the time; but actually it contains at least twice that number in all because there are shots without any timepiece, too. The sheer task of

compiling and splicing them is a heroic act of patience. But, above all, the continuity that accomplishes a semblance of narrative is truly breathtaking. For example, a woman knocks at an apartment door; the cut shows the interior and a man opening it but this is from another film. Similarly, a man starts a car, checks his watch, and then the next shot shows another car speeding on a highway with a different character at the wheel from another film. A woman pours tea but another woman drinks it in different setting of another shot. Different segments from one film are at times distributed over a length of passing time, some without a time piece in it, but always synchronous with the real time regardless.

Ideally, one should view it in its entirety, all day and all night, or at best, say, from 5:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. continuously. Otherwise, one should catch in two to three hour segments several times to cover as much of the whole film. A DVD version of the film would be impractical without a means of synchronizing it with real time. But a catalogue raisonnée listing all the filmic sources minute by minute would be useful for film buffs, for whom the work is an inexhaustible source of pleasure. Even within my two-and-a-half hour of viewing, I recognized, without being able to identify immediately, numerous films from my stock of knowledge. It was a tremendous pleasure to encounter familiar faces of actors from the past, near and remote, even if, again, I was unable to quickly remember their names since the shots are flashed only instantaneously and go fast.

In the course of two-and-a half hours we are also made aware of the situations when we are alert to the elapsing time; awakening in the morning or from a nap, waking someone up, going to work or school, waiting for and catching a bus or train, a rendezvous of all kinds -- an appointment, a date, a tryst, a conference, a meeting, and any consorted action requiring the watches to be synchronized, completion of a task, looking up a large clock in a public place, like the Big Ben, and later in the day, getting up to start cooking dinner, checking on the return of a family member, remembering a TV program to watch, the movie showtime, or a curtain time at a theater, preparing to hit the sack, and waking up in the middle of night. Conversely, we are reminded of those instances when we forget the passing of time as when we are deeply engaged in work, play, reading, or daydreaming.

Daydreaming, indeed, quite aptly describes the experience of watching Christian Marclay’s cinematic masterpiece, Clock.

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

Older and wiser

When we are older and wiser, we get to know more; but, as we know more, we also realize how much more there is that we don't know, and therein lies the true wisdom. Frustrating as this realization may be, it also opens up an endless opportunity for learning.

Thursday, January 3, 2013

Il Barbiere into The Barber

The Barber of Seville, sung in English, which the Met proudly mounted this season, not surprisingly deflated Gioachino Rossini’s sprightly opera, Il Barbiere di Siviglia. The problem was the English language. Every language has its own cadence, and, to the extent Rossini matched his music to the rhythm and flow of the Italian language in Cesare Sterbini’s libretto, the English translation, despite J. D. McClatchy’s effort, brought out blatantly the discord between the language and the music. This is not to say that Italian libretti cannot be successfully translated. It just so happens that the clarity of vowels, essential in an opera buffa, in particular in those patter passages, are hard to come by in English which is rich, instead, in slurs and schwas (those unstressed vowels). The contrast is evident in the very word in the title; il barbiere, pronounced in five crisp syllables (il-bar-bi-e-re) comes out as the barber, pronounced in three syllables of a schwa-slur-schwa. Note how the word like padre becomes fluffy in father and qui e la comes out drawn out in here an’ there; and gioia e pace peters out sonically in joy and peace. English words more frequently end in a consonant whereas Italian words almost invariably end in a full vowel. It’s not that for these reasons English is not suited to the opera. Purcell, Gilbert and Sullivan, and Britten glorified their language in their operatic works; Cole Porter and Stephen Sondheim wrote lyrics and music to fit the English cadence. Though the English Barber, abridged to two hour from the three-hour long Barbiere, was trumpeted to be a family fare for the Holidays to suit the kids in the audience, we must recognize that children are often more responsive to the comic effect of nonsense words and, therefore, to the succession of brisk syllables the Italian Barbiere delivers with gusto. They grasp the sense of the sung phrases if they failed to understand their word-by-word meaning. The Barber sounded flat like the birra that lost its fizz; it was un barbaro di Siviglia.

Tuesday, January 1, 2013

Two Townhouses

Across from my apartment window I see two five-story townhouses. At a casual glance they are a contrasting apri, one of plain buff-colored wall and the other of red brick. It does not require much scrcutiny, however, to see that they are twins built together at the same time, most likely around 1870 (or else a couple of decades later in a retardataire style); but the unit on the left was subjected to modernization in 1950s by stripping the beautifully decorated cornice (together with the chimney stacks) and painting over the brickwork as well as the prominent limestone keystones and lintels. The windows of the upper three stories were slightly shortened in the process, and the ornamental relief panels between the third and the fourth stories were filled in to accommodate window air conditioners. More drastic changes wwere effected on the ground level. The entrance stoop and the arched portico were removed and entrance doorway was lowered to the street level. This was a typical facelifting popularly adopted to make the facade plainer and more in tune with the taste of the time.

Fortunately, the landlord of the right unit evidently liked the Victorian look well enough to keep it intact. If you look closely the second level of the fire escape on the left, you will find a honey tabby cat comfortably napping.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)